Developmental trauma is a term used in psychology literature to describe significant adverse experiences—such as abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional), neglect, or other profound experiences of harm—that occur in childhood during vital stages of cognitive, emotional, and social development.

There are many ways to support developmental trauma survivors. Some methods are well-known, while others are not. While researching my book, You Don’t Need to Forgive, I discovered six unique ways to support survivors:

1. Respect Family Estrangements

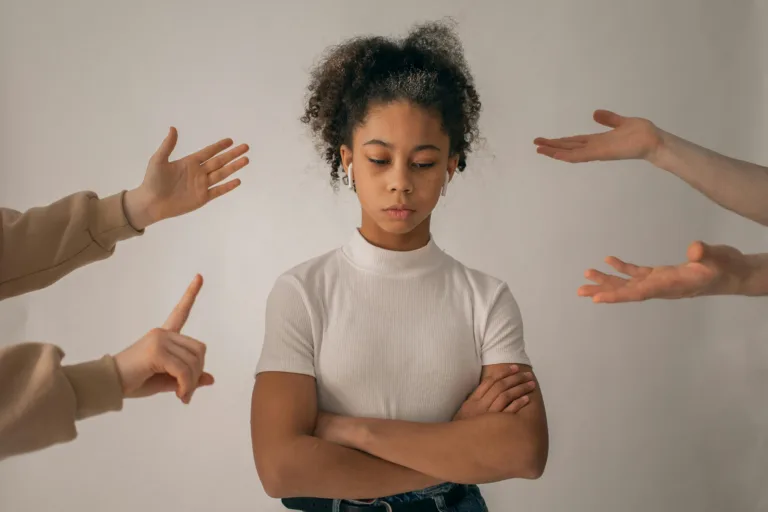

Developmental trauma can cause survivors to choose to be estranged from their families. Many survivors must initiate and maintain family estrangements to achieve the physical and emotional safety that’s needed to engage in trauma recovery. Family estrangements can be brief or long-term, or they may last forever. Unfortunately, family estrangements are highly stigmatized in many societies, cultures, and religious communities. To support survivors, try to respect their decisions to remain estranged from their families or certain family members, even if you do not understand or agree with them.

It’s rare for survivors to reconnect with their family when they are pressured or forced to do so, and when they do reconnect under these terms, that connection is usually short-term. Be aware of your biases and judgments regarding family estrangements, as these could negatively impact your ability to support a survivor. If you are a survivor’s family member, know that your family experiences might differ from those of your family member who has chosen estrangement.

2. Accept That You May Never Know Their Complete Story

Developmental trauma survivors might not have a complete narrative to share with you. Sometimes, traumatic events and experiences occur when we are very young and cannot store cognitive memories. And even if survivors experienced traumatic events at an older age, these experiences aren’t always kept in the brain as a complete cognitive memory. Some survivors might have physical sensations or sensory experiences connected to past experiences instead of cognitive memories. Moreover, additional factors make it impossible for survivors to access full memories, such as experiencing dissociation while the event was occurring and experiencing the impact of intergenerational traumas that may have happened before they were born. You might never know a survivor’s complete story because they might not fully know it or be able to put it into words themselves. The brain has many sophisticated defense mechanisms designed to distort or block our access to complete memory narratives.

Survivors also might not need to tell you their stories. They may have told their story so many times that it is no longer helpful for them to do so. They may find talking unbeneficial and instead rely on other coping mechanisms. In addition, sharing a trauma narrative might be harmful to some survivors, as they might feel as if they are reliving their trauma in the present, or they might not feel safe enough in their relationship with you to share their story. Regardless of the reason, consider accepting that you might never know their complete story.

3. Address Your Trauma

Your trauma responses can be triggered by or may intersect with, another person’s trauma responses without your awareness or control. Imagine this: your loved one is a developmental trauma survivor who avoids conflict. They were surrounded by constant battle as a child, and now as adults, they flee whenever someone is upset with them. When they escape from you, you fear they will abandon you, just as your mother did when you were young. You run after them and do everything you can to keep them engaged in the conflict so that you may resolve it and they won’t leave you. This pattern is unlikely to healthily repair your relationship repair with them, as you are both experiencing trauma responses that are more likely to intensify rather than assuage one another.

There are many ways to address your trauma to support other survivors. You can process your experiences by sharing them with others, writing about them, or creating works of art. You can engage in physical interventions to that processing trauma, which is accessible in your body. You can also participate in individual, couples, or family therapy. Participating in trauma recovery can improve your relationship with a trauma survivor.

4. Respect a Survivor’s Lack of Forgiveness

Forgiveness is often seen as a universal cure for anger, resentment, and trauma. In reality, there is no universal cure. While writing my book, You Don’t Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery On Your Own Terms, I learned that there are many reasons why survivors may not be capable or willing to forgive their offenders, such as not feeling safe, needing the time and space to recover, and having to combat societal, cultural, or religious pressures to forgive. It can be helpful to be aware of your own experiences, perceptions, and biases regarding the concept of forgiveness so that you do not force these upon survivors.

You might be tempted to pressure or encourage survivors to forgive their offenders for helping them recover. This pressure tends to be more significant when the offender is a biological relative, a close friend, a spouse, or a person of perceived importance. However, pressuring survivors to forgive is rarely successful and typically only motivates fleeting and inauthentic gestures of forgiveness. Instead, respect their resistance to forgiveness even if you disagree with it. This respect can help you foster and sustain a safe relationship with them.

5. Understand Unmet Attachment Needs

Developmental trauma often hurts a survivor’s ability to attach to or participate in healthy relationships with others because their attachment needs are unmet during key stages of development. These attachment struggles can be expressed as a pervasive fear of abandonment or rejection (which may manifest through either fawning, controlling, or conflict-avoidant behaviors), an inability to accept or extend reciprocity or intimacy, a pattern of sabotaging relationships or of starting and engaging in conflicts, or as difficulty with establishing healthy boundaries or with respecting the boundaries of others. It’s also a good idea to assess your unmet attachment needs and how these may impact your relationships.

Attachment issues can appear as relationship patterns that are toxic or stigmatized, such as co-dependency, enmeshment, and antisocial traits, which can impinge upon your relationships with survivors. It’s essential to be aware of a survivor’s particular attachment struggles, as this will likely impact their relationship with you and others. This understanding does not excuse any of their actions, but it might allow you to extend empathy to them, which will help them in their recovery.

6. Provide a Healing Relationship

Trauma can be healed within relationships. Yet, these relationships must include safety, empathy, attunement, and co-regulation, which is a process by which you use your emotional state to help survivors regulate their emotional states. One of the best ways that you can support a developmental trauma survivor is to provide them with repetitive healthy relational experiences that address their unmet attachment needs. This does not mean that the relationship shouldn’t include conflict. All healthy relationships involve conflict and are strengthened by effective conflict mediation.

How can you provide a healthy, healing relationship? First, focus on establishing and maintaining safety. You can do this by listening, being physically and emotionally present, expressing empathy, vulnerability, and unconditional acceptance, and respecting their agency. Once safety is established, focus on providing co-regulation. For example, suppose a survivor flees when conflict occurs instead of pressuring them to continue to engage in the competition. In that case, you might remain calm and take a break from the argument or altercation, validate their emotional responses, and engage in coping skills with them to help manage their emotional/trauma responses.

Developmental trauma survivors need your support. Consider implementing these lesser-known methods to support them.

Purchase my book, You Don’t Need to Forgive

Sign up to get your Free eBook: 25 Anxiety & Trauma Coping Hacks

Hire me to speak at your event! Contact Me

Looking forward to content.

You said: There are many reasons why survivors may not be capable or willing to forgive their offenders

I don’t like the fact you framed this as we (I) am not capable or willing to forgive. Healing from family trauma is very hard work. It’s about looking at the truth of what was done to me. NOBODY has ever asked me to forgive the man I was in love who beat me up. It’s not that I forgave him…I just don’t care anymore.

I don’t need to forgive my family. I am healing because I can now stand in my truth and see things for what they are.

On the other hand, my family (siblings and mother) are still caught up in the dysfunctional dynamics. I do have compassion for some of them and I am no longer angry because I’ve done the very difficult work of facing it all. I am now no contact with all of them and my life (finally) is getting better every day.

This forgiveness S*** is for minor stuff. OOps you’re late for supper again. I forgive you.

I nearly drove myself crazy with Complex PTSD symptoms thinking and being told that if I just forgave them it would all go away. NOT TRUE!

I have a quote on my armoire that I really like. Not sure where I got it.

Denial of truth creates suffering. Truth demands itself be heard.

They don’t want to see the truth or hear the truth. There is nothing to forgive. It’s about accepting the awful truth.

I am standing in my truth!

Great job site admin! You have made it look so easy talking about that topic, providing your readers some vital information. I would love to see more helpful articles like this, so please keep posting!